“I was personally impressed by the motivation and dedication of the team for this discovery work, and the commitment by all to the articulation of user needs. I have spent some time reading through your documentation online, and I have yet to see something of this magnitude across Defence.” Dr Silvia Grant Head of User Research at DDS

On Friday 25 March Army HQ’s Deployed Applications Group volunteered to be put through their paces at a Service Assessment for their Land Deployed Applications Discovery (LDAD).

Whilst not a formal Service Assessment, it was run as such with assessors and observers from Defence Digital Service (DDS) and observers from the Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO).

The definition of a Discovery

The Government digital service manual defines discoveries as the phase run initially to understand a problem that needs to be solved, before embarking on the creation of a service. In Dr. Silvia Grant’s recent Defence Digital blog post ‘Rediscovering Discoveries’, reference is made to the Foundry Discovery and how teams can inadvertently uncover a set of problems, analogous to the tip of an iceberg. This is applicable to the LDAD findings, insomuch as the team have unearthed a vast range of both in-scope and out of scope issues, either directly or indirectly connected.

Understanding users and their context

The multidisciplinary team of Military, Civil Servants, and Contractors interviewed over 175 end users and 58 enabling users during the Discovery.

“The team displayed mature agile and digital ways of working. Consisting of a full multidisciplinary team, the project was able to zoom into specific problem spaces where required, with precision and skill.”

“This is the first time that army research has been user centric and is a massive achievement’

Capturing the battlespace

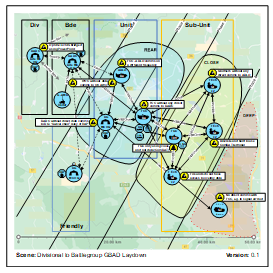

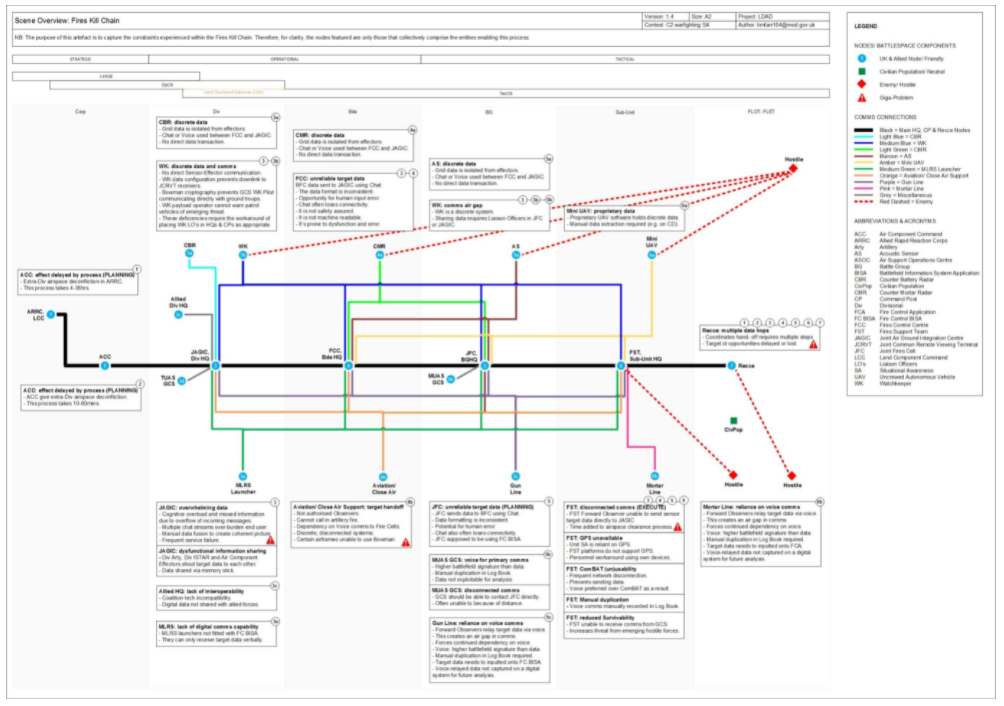

The context of the Discovery centred around C4ISTAR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Information/ Intelligence, Surveillance, Targeting Acquisition and Reconnaissance) within the deployed warfighting environment, and the passage of information between users and nodes needed to support this.

User-centred design (UCD) often turns to artefacts such as personas, user journeys or service blueprints to relay user problems and needs. However, we found these options could not truly capture, say, the shared experience of a battlegroup of almost 1000 people, tasked with achieving a series of effects, equipped only with inferior means of communication and tooling.

Therefore, we next considered standard military devices, such as vignettes and scenarios. However, we decided against those owing to preconceptions about their use, concluding they were unable to capture the type of threaded interdependencies we needed to communicate.

Variables and visualisation

The more we learned about the extensive dysfunction of the UK army’s software, hardware, comms, equipment, culture, doctrine and training, the more we realised how there exists an interwoven, overlapping conflation of factors. So, under the steady stewardship of product manager Major Chris Bulmer, our team created the concept of ‘Scenes’. In brief, a scene captures an activity, undertaken to achieve a military effect and it can result from one or many user research sessions, from which several user journeys are woven together within a wider ecosystem. A scene helps demonstrate how individual actors, groups and entities interconnect, and the issues encountered during the lifespan of that specific experience.

A scene commonly:

A great deal of the scenes we created revolve around the need for efficient communication networks providing accurate and timely situational awareness. An accompanying visual – or ‘scene overview’ - depicts the arrangement of components (nodes or ‘force elements’) contained within the scene, the touchpoints between them, and pertinent supporting information about the problems involved.

This visual graphic can also be interactive, so force elements featured can contain a hyperlink to source information. Or, there can be links to other contextual information, such as pain points gathered within an overarching Problem Statement page.

The strength of these scenes lies in how they enable us all to look at the status quo, holistically and objectively. We can see precisely how factors and variables combine to produce a specific outcome. We can then take this understanding and analyse it further, to look and find solutions to the issues our forces are facing.

Ultimately the exact format of the visualisation element was always driven by the need to convey knowledge and understanding in that context. The best way to explain the users challenges. As such each could be different in exact format and style. This is the main goal and our investigation is beginning to come to fruition. We will share further findings from our discovery in these articles, over the next few weeks and months.

The assessment panel concluded:

“The team has mapped very complex user needs in a number of impressive artefacts, multilayer user journeys, and visualisations”

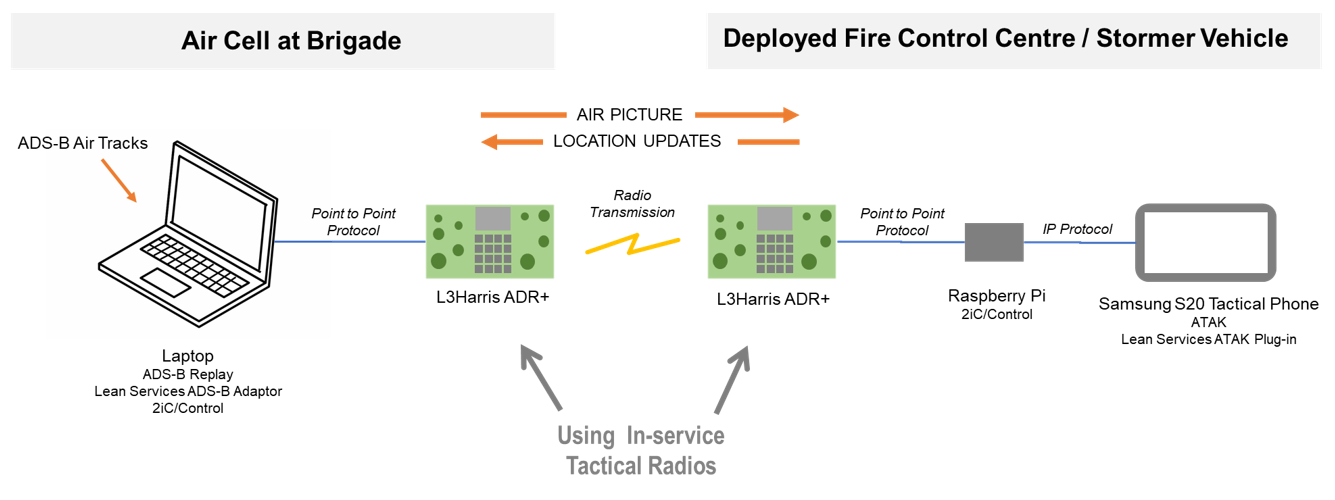

Technical Discovery

The team also carried out a short technical discovery using in-service equipment to solve a Ground Based Air Defence problem. The plug-ins have been uploaded to the Army Digital Services code repository.

This also gained praise form the assessment panel:

“Some alpha-stage prototyping was undertaken as technical demonstrations, in particular with bridging a user need on supplementing voice-first comms within Army using L3Harris ADR+ radios, Raspberry Pi control, and ATAK plug-ins as a successful 12-day prototype solution. This demonstrated not only the potential ease of experimenting comms between Air cells and stormer vehicles by identifying 150 air tracks per minute, but was a practical demonstration of how existing data can be transferred securely and efficiently, resolving a clear user need. This quick prototyping also exemplified good cross-government working practices by working in the open, and sharing new code.”

Understanding constraints

The team also needed to understand the constraints of the battlespace:

“Constraints regarding doctrine, ways of working, military protocol, working at higher classifications, domestic and international interoperability, and commercials/procurement processes were expertly summarised, as well as deeply understood by the team.”

Research ethics

During our research we had to navigate conflicts of interest between the intentions of individual programs, the relationships between Army HQ and Field Army, and even Civil Service procurement processes (need for transparency) and suppliers profit motives (poor delivery performance record and indiscriminate use of obfuscating policy such as ITAR).

We were conflicted in our appreciation of our research data and subsequently we wanted to share our findings with people who could do something about it, but we were struggling with stakeholder engagement.

We also experienced clashes of ethical frameworks – ethic of obedience (deontology) i.e. the organisations hierarchy, ethic of care (utilitarianism) i.e. empathic sense of what benefits the most people and harms the least and ethics of reason (virtue ethics) i.e. rational judgement based on wisdom and self-control.

These manifested as conflicts of principle such as truth vs loyalty (military reward model and its intolerance to bad news, amplified by the military rotation cycle). The biggest challenge was balancing conflicts of rules vs principles (aligning Army values, Civil service values and Agile values, whilst respecting the chain of command). And for our research participants, we had to be particularly careful in managing their ‘revelation-ary’ experience as we discussed sensitive topics regarding their roles within a larger integrated context of war fighting.

“The team grappled with some important ethical conundrums in its research space, including whistleblowing on poor working practices, behaviours and technology use. The dedication of the military product owner has been essential to tackle these issues appropriately. The moral and psychological wellbeing of the team was also being looked after during this long discovery and encapsulates the ethical questions to consider when exploring multi-faceted problems spaces in Defence.”

Identify improvement you might be able to make

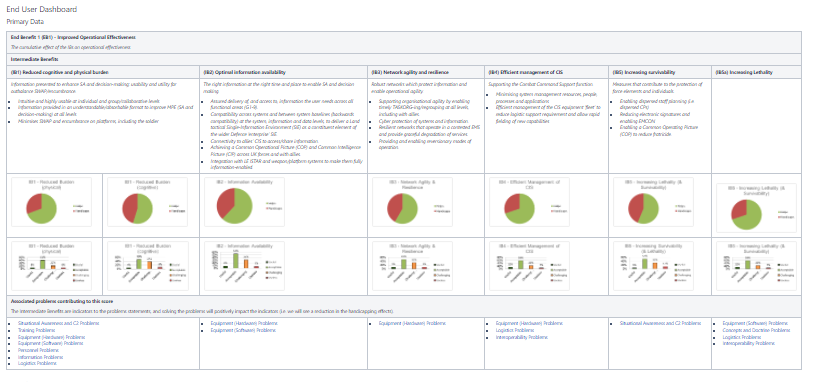

In the absence of any consistent performance measurement between the in-service applications, systems and software and the benefits they were intended to provide the project needed establish a baseline set of measurements across the deployed space.

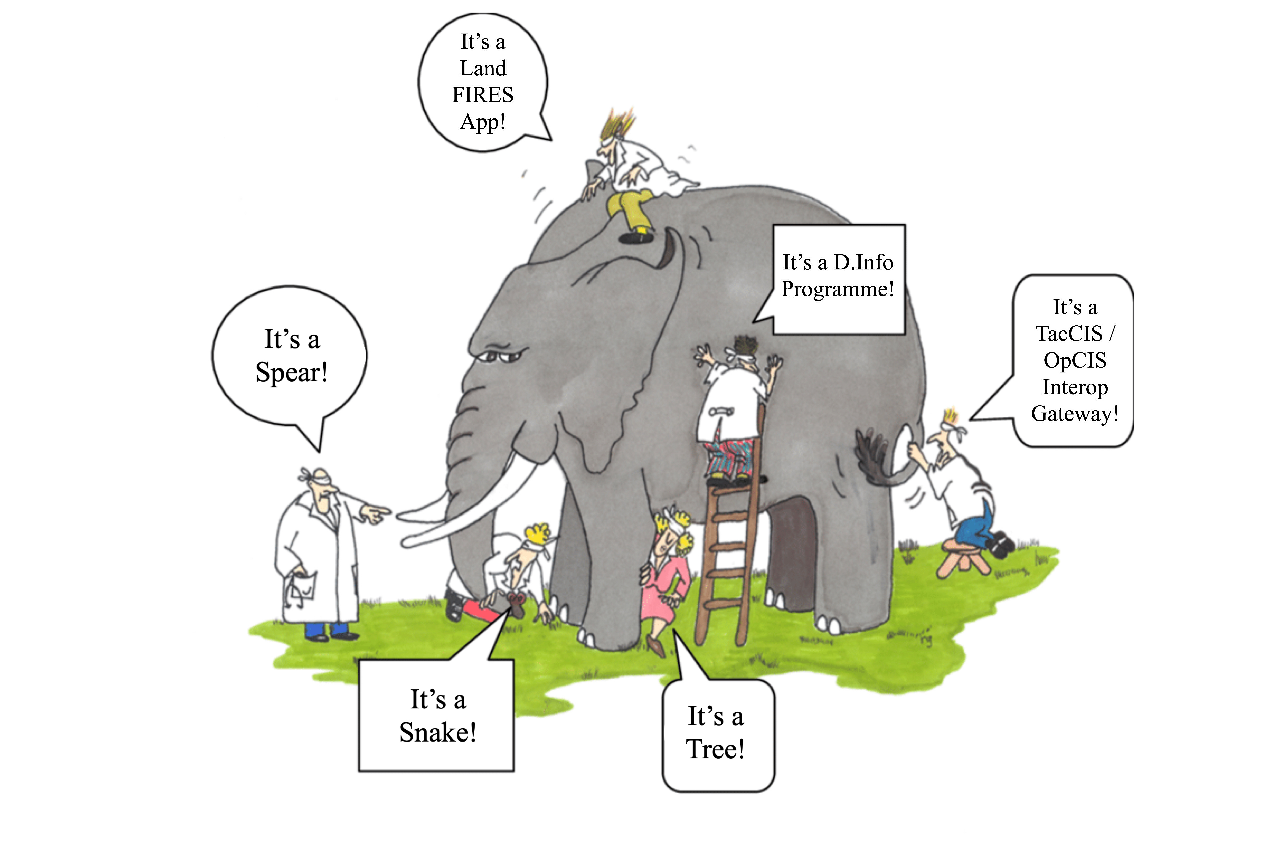

One key challenge was defining the deployed space in the context of a service. As a complex, high risk socio-technical system, there were significant difficulties in drawing a line around people, processes and equipment that deliver operational outcomes. As such, the deployed space was defined as ‘Pete’s Dragon’ analogous to Gary Larson’s ‘Far Side’ cartoon elephant below (with a few tweaks), in that, depending on your operational view, the service had different working parts, qualities and intended outcomes to your colleagues in the same deployment.

Another key insight came in the form of establishing the logical relationships between effective warfighting (as an organisational objective) and the dependency upon the end user performance (and experience) and the effective delivery of the service (dependent upon the performance of the enabling users managing and operating it). In this way we were able to relate both enabling user and end user experience to organisational outcomes.

Using the framework, we were able to derive two surveys, drawing on the qualitative research findings and linking them with the performance measures. One survey targeted the end users and their experience of using the service to do their job. And the other survey targeted the enabling users, and their experience of implementing and managing the service to provide the end user experience.

We were then able to use Net Promoter Scores (NPS) for the end users and the enabling users to draw a comparison between Army’s tactical services and Industry.

In using this framework the LE TacCIS programme, and the other large programmes with digital components, now have a more mature approach to measuring service performance, which is suitable for scaling, producing coherence and alignment from projects to encompassing the entire Army change and Business As Usual (BAU) portfolios.

Summary

“The user research is overwhelming”

The LDAD team are the first in Defence to conduct a Service Assessment for a warfighting service and to conduct a Strategic Discovery, they met all aspects of the Assessment. The assessment panel concluded:

“Despite being a mixed team of contractors, suppliers and military, the team displayed a fantastic amount of personal dedication and commitment to this discovery. The outputs of discovery are conspicuous, and of clear re-use across Defence, particularly in mapping the military user pain points (which will be persistent across Land, and other domains).

The panel was impressed by the quality of the outputs, as well as the amount of ground covered by the discovery. The radio prototype proof of concept was an effective demonstrator for how existing data and tech can be harnessed in-house to resolve recurring pain points.”

Leave a comment