In the first of a 3-part series, the Army Design Ops team and Army Digital Services (ADS) Deployed Application Group; who are pioneering user-centred design and design thinking within Defence, share some key insights from working on a discovery phase in the deployed context.

Forming the Team

The ADS Deployed Applications Group are leading a programme to develop a suite of applications suitable for both conventional and high latency networks in the deployed space.

Concurrently, the Army Design Ops team were working to introduce user-centred design into Army IT and software development. They were also writing an Army Service Manual (based on the Government Digital Service Manual) and developing an Army Design System in partnership with Royal Navy Digital.

The two decided to collaborate – pooling resources to form a multi-disciplinary team – and to use one of the application’s discovery phases to test the processes and best practice being developed by Army Design Ops team.

This also gave the Deployed Applications Group much-needed support in the form of an exploratory dry-run alongside an expert team which would then inform all subsequent discovery phases.

Getting ready for Discovery

Tasked with examining the feasibility of an app-based solution for Logistics Command and Control in a warfighting context, we quickly identified the need for a pre-discovery period of planning and preparation (or ‘mobilisation’). It’s a similar exercise to what our friends at Royal Navy Digital call ‘First Look’.

One of the main challenges in mobilisation was to create an initial problem statement which encapsulated the scope of our investigative work. We came up with this:

“There is currently no co-ordinated, consistent, accurate and singular digital logistics system that supports Reports, Returns, and Requests (R3) from Unit through to Division. This results in the absence of visibility of reliable and current data that would enable Commanders and their staff to make informed decisions with regard to the Command and Control (C2) of logistics, as well as equip logistics personnel of all types, at all levels, and from different [nations] with the means to effectively sustain the fight in a simple, agile and efficient manner.”

Most non-military personnel are probably now asking themselves what are R3 and C2 and are probably thinking of civilian Logistics. Reports Returns and Requests, or R3, is a common military acronym which, for non-military readers, probably means very little. Essentially it is a catch all term to cover information flows that are maintaining situational awareness and requests for (in this case) logistic support or material and routine updates.

Command and Control, or C2, is another common military acronym which covers the high-level ownership and low-level direction of military personnel and assets. C2 relationships are defined by very specific definitions and any operation will have very clear and unambiguous C2 relationships. To be able to effectively practice C2 and R3 however you need the communications systems and supporting software tools to enable it.

Logistics in the military has considerable similarities to logistics in the civilian world, however getting the right quantities of ammunition, food, water, fuel, spare parts and medical supplies to the right place at the right time on a battlefield is much more challenging.

Specialist units from the Royal Logistics Corps work alongside a large number of logistics specialists from the Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery on the move across hundreds of kilometres to enable this and all activity needs to be ruthlessly synchronised.

It should be no surprise that we found that the problem statement was much too large for the 8 weeks available to us and needed further iteration. Smaller was definitely better.

The problem statement did allow us to better understand the context within which we were working. Clearly, this was no ‘greenfield’ opportunity, so we selected Sutherland & Schwaber’s ‘Scrum’ as the agile framework which would best serve iteration and improvement to existing products and services. This immediately gave our team an agile cadence to work with (daily stand-ups, bi-weekly show & tells, retrospectives, and planning sessions) and a shape for our Jira-based planning board.

We then used Jeff Gothelf’s Lean UX Canvas to help us explore the detail behind the problem statement with our senior stakeholders. It’s a great tool, but we found it needed adaptation for use in the Defence context. Military personnel struggled with the business focus, and references to customers, channels, and competitors, so the team backlogged a task to create a Defence-specific version of the canvas.

We captured our collective thoughts on the Lean UX Canvas template using Lucid Spark, a fully featured digital whiteboard that is one of the few that works over MODNET (Defence’s corporate ICT system) and that integrates with Jira. Indeed, Army Design Ops worked with Lucid Spark’s team to specify requirements and beta test the integration.

Completing the Lean UX Canvas helped us identify several issues to be resolved in mobilisation:

- identifying and gathering publications for desk research, such as relevant parts of Doctrine and handbooks

- gaining access to mission threads and vignettes, if they exist, from business architects

- identifying parallel in-flight projects, their scope, opportunities to collaborate, and to improve our overall situational awareness

- identifying logistical enablers and blockers, such as near-future exercises that could provide research opportunities, or military leave periods that were effectively research blackout periods

- identifying our stakeholders and key users for priority access

- recruiting suitably qualified and experienced assessors for the end-of-phase Service Assessment (a Government Digital Service construct that is akin to a Military Judgment Panel)

Gaining access to users for research

The main effort in mobilisation, however, was to secure access to users for research activities. In Defence, this is a very different proposition to finding users in either the public or private sectors. On the positive side, we didn’t have to hire market researchers to find people in our target segment, or to pay attendees to take part in research sessions. Instead, we encountered a different set of issues.

There are specific governance and ethical considerations when carrying out research in the Defence context. Unfortunately, it was unclear to what extent, if any, guidance in the form of JSP536 (Defence research involving human participants) should apply to our activities. A clarification request was submitted, and in the meantime, we took a principled but pragmatic approach.

The formal processes for securing access to Army personnel have relatively long lead times that just don’t support fast-paced activities such as an Agile discovery phase. For example, a Demand Signal into the Land Operations Centre (LOC) may take up to 18 months to generate a formal Task Order, depending on the number and specialisations of personnel required.

Clearly, those processes and timescales aren’t suitable for our purposes, which is why it is very important to have well-connected military Product Owners, Service Managers and subject matter experts within the team to gain access to users informally. In our example, we were fortunate to benefit from the support of the Deputy Chiefs of Staff of all three of the Army’s Armoured Brigades, plus our Product Owner, Major Hugo Kekewich and lead user Lieutenant Colonel Darren Fisher, who facilitated access to personnel within 101 Logistics Brigade.

Matt Odell and Mike Linskey from the Army Design Ops Team, under Major Andrew Campbell, had previously piloted small-scale user research sessions for a different project with 1 MERCIAN, an infantry battalion, in their camp at Bulford. We knew that to get the most out of this opportunity, we needed to go where the users were. This would help us to experience their context and evidence-rich environment in a much more immersive way.

There is an administrative overhead to in-barracks or on-exercise activities in the form of security vetting and applications for location access. Depending on where it is intended to carry out research, anything from a Counter Terrorist Check to Developed Vetting may be necessary, with varying degrees of paperwork and lead times involved that need to be factored into planning. At a minimum, researchers should expect to complete a Baseline Personnel Security Standard (BPSS) and will probably be required to sign the Official Secrets Act.

It is also worth noting that there are restrictions around taking evidential photographs of military personnel, their equipment, and activities, or even just on MOD land, that are over and above the usual ‘permissions’ that a user researcher should plan for. It is important to obtain formal authorisation from a Commanding Officer and any military personnel who are likely to be photographed, and to use MOD-supplied camera equipment. The penalties for non-compliance with the Official Secrets Act are severe.

A quick win we identified early in mobilisation was to issue a survey to members of the Army Logistics community, both to gather early research collateral but also to see who was keen to contribute. We were able to identify potential survey participants using our draft stakeholder map and the knowledge, experience and informal contacts of our product owners and other stakeholders. Fortunately for us, it is still true that much can be achieved using ‘mate’s rates’ within the Army.

We designed and built the survey using SurveyMonkey, after checking it was accessible on a range of MOD-issued and personal devices. Alternative survey tools that we considered failed this check.

As part of our governance considerations, we identified the need for SurveyMonkey or a similar tool to be appropriately licensed by MoD and accredited to store personal data in compliance with their Personal Information Charter. In this instance, our workaround solution was to use separate forms (MS Forms and hosted on MODNET) to capture participant’s personal data and research agreements.

In addition to issuing the survey via email on MODNET, we also published a link on Defence Connect, an enterprise social network used as an internal communications channel by the Army.

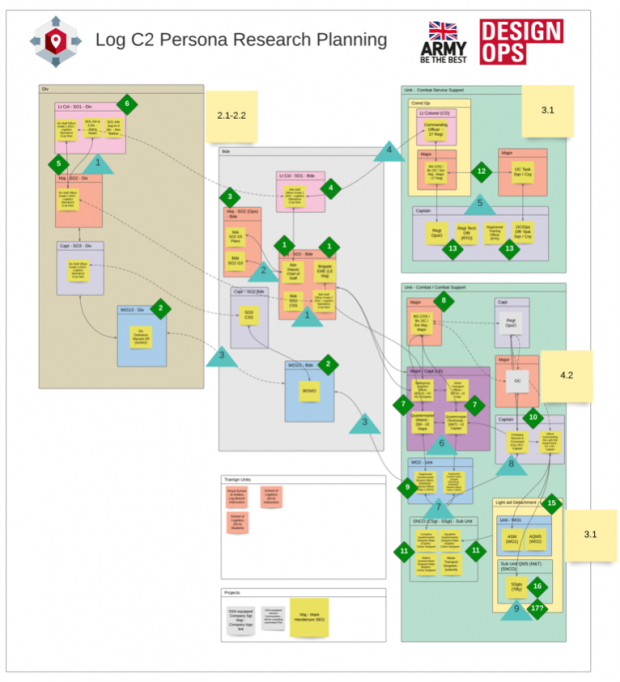

Analysing the results of the survey led us to conclude that the ‘traditional’ focus on producing personas at the beginning of Discovery might not have been the most effective use of our time. Although initial stakeholder mapping had identified 70+ distinct roles across multiple regiments and corps that were within our scope, we learned that there was a great degree of homogeneity which would render typical persona formats relatively useless.

Equally, a Target Audience Description (or TAD), a typical artefact from a Human Factors Integration Plan, was also found to be too generic for our purposes. We eventually solved the problem in a later stage of discovery, which will be covered in our second blog post in this series.

We were able to identify potential research participants for interview using a combination of our stakeholder map; a basic laydown illustration which helped us understand the distribution of logistics users across Division, Brigade and Unit; plus, the aforementioned ‘mate’s rates’.

Being prepared to adapt

Towards the end of our mobilisation phase, the announcement of further COVID-19 restrictions plus the signposting of the second national lockdown caused a major re-focus from predominantly in-barracks activities to fully remote user research.

Overnight, we pivoted from booking physical research locations, equipment, stationery, travel, and accommodation to testing video conferencing and digital research tools to make sure that those people that were unlikely to have MODNET access could still take part.

We will expand on what we learned about carrying out user research remotely in a deployed context in Part 2 of this blog.

Our final mobilisation task was to invite participants to a series of online research sessions to take place in the discovery phase. The invitation was deliberately written in a format familiar to military personnel –an Administrative Instruction – that provided:

- background to the task

- aim of the research session

- registration information (link and QR code for a SurveyMonkey form which documented the user’s agreement to participate)

- list of participants by role

- preparation required

- scheme of manoeuvre (dates and times)

- co-ordinating instructions (location)

- researchers and military personnel available during the session

- main events list (session structure and approximate timings)

- command and signal (communications methods and researcher’s contact information)

Even that process had a twist in the tail. Unlike public and private sector user research, where it is usual to receive a list of named research participants with supplied contact details and agreed session times, we were still working to roles and appointments in some instances.

In practical terms, this meant that we had no idea who would turn up for some of the scenarios we wanted to explore. In addition, some of the named participants initially responded by offering a deputy or to pass the invitation to an IT representative under the assumption that this was a G6 (Communications, Information and Systems) task.

This is a good example of the compromises and pitfalls a user researcher will need to consider when working in the Defence context.

What we achieved in the mobilisation phase

At the end of our 2-week mobilisation phase, we had:

- drafted our problem statement

- formed an initial, educated view on who our stakeholders and users were

- established our priorities

- allocated a team

- set up our physical and virtual working environment

- issued invitations to agile ceremonies

- created a research plan

- set up a framework for delivery

- created a task backlog on Jira, our agile planning tool of choice

- issued invitations to remote research sessions

You will be able to read more about mobilisation in the alpha version of the Army Service Manual which is to be published shortly.

Our next blog post will explore the practical side of the discovery phase and in particular the lessons we learned in carrying out user research in the deployed space.

Leave a comment